Updates and impact

AH(p)!: why the current Affordable Homes Programme has failed (and why the next one can't)

Published date: 5 June 2025

Andrew Soar

Senior Digital Campaigner

On 11 June, the funding for the successor to the 2021-2026 Affordable Homes Programme (AHP) will be announced.

At Shelter, we think the current Affordable Homes Programme has failed. Here's why it hasn't done what it says on the tin – and why the next one must.

First, what is the Affordable Homes Programme?

The Affordable Homes Programme is the way the government directly funds and helps build social and affordable housing. In the last three years, it's accounted for around 40% of all of the social and affordable homes built in England. The other social and affordable homes delivered in England are mainly built by private developers through section 106 agreements (e.g. you have permission to build 100 homes, as long as ten of them are affordable).

The current Affordable Homes Programme (2021-2026) had a budget of around £11.5 billion. It initially had the aim to deliver 'up to 180,000 affordable homes' over five years. This was then revised down to 110,000-130,000 affordable homes in July 2024.

Why do we need an 'Affordable Homes Programme'?

Social homes delivered by private developers – through section 106 – make up around 1.73% of total housebuilding numbers. So, at current rates, you'd need to build over five million homes to get the 90,000 social rent homes a year we believe are necessary to end the housing emergency.

And, in addition to this, private developers will never build enough homes fast enough to reduce prices – it's simply not in their interest to see their profit margins fall. We're seeing this across the country, with developments paused because the homes aren't selling. That's why the government needs to step in and build homes people can genuinely afford – social rent homes.

Why do we need social rent homes?

The number of children living in temporary accommodation has increased by over 46,000 in three years. It is now over 165,000 children, costing councils £6.2 million a day. Based on current trends, we project there will be 206,000 children in temporary accommodation by the end of this parliament, costing councils £10.7 million a day. To provide homes for those in temporary accommodation, those stuck in private rental properties they can barely afford, and those on low incomes, a new generation of social rent homes is the answer.

So, with the successor to the Affordable Homes Programme just about to be announced, let's learn some lessons from the old one, shall we?

Lesson one: not enough money

£11.5 billion sounds like a lot of money. But over five years, to build expensive things like homes, it's actually very little. It's nowhere near enough money to end homelessness – considering we need to deliver 900,000 social homes in 10 years. For context, the government spends around £1,023 billion a year. So, we've been spending, very roughly, 0.2% of our annual budget on building 'affordable' homes.

We need to move back to a system where we invest in social housing and recycle the social rents (including housing benefit) to maintain and build more social homes. The current system, born out of a chronic underinvestment in social homes, relies on siphoning off billions of pounds in public money each year to private landlords – this simply cannot continue.

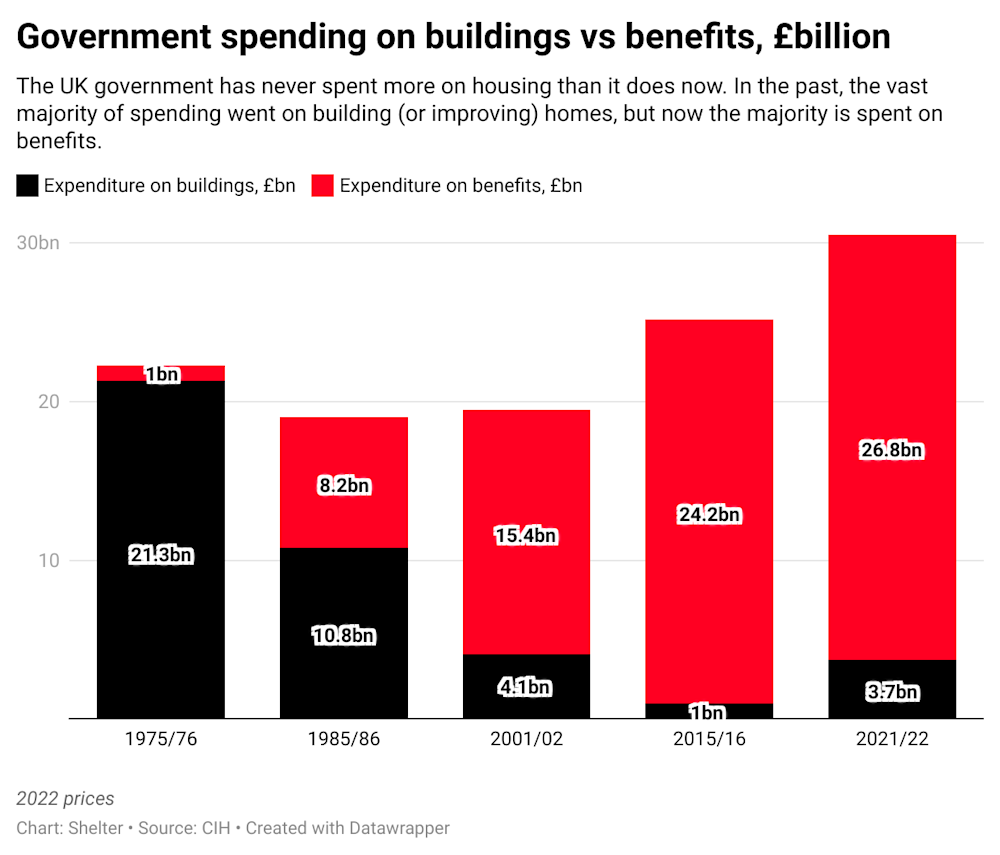

As shown in the 1970s (see graph below), investing big in social housing while continuing to subsidise private rentals where needed makes far more financial sense. In the 1970s, we spent the vast majority of the housing budget on building hundreds of thousands of social homes every year. Now, the graph is reversed, with only £3.7 billion of the £30.5 billion spent on housing going to building new homes.

The UK government has never spent more on housing than it does now. In the past, the vast majority of spending went on building (or improving) homes, but now the majority is spent on benefits.

We believe the next Affordable Homes Programme must build a new generation of social rent homes to tackle the spiralling costs of housing benefit and temporary accommodation. The government should invest in 90,000 social rent homes a year for 10 years to end the housing emergency.

To do this, it needs to earmark a minimum of £30 billion to £38.2 billion for the first five years – or around 0.7% of annual government spending.

Lesson two: building the wrong houses

Shared Ownership, Affordable Rent, Social Rent, First Homes and numerous other tenures all sit under the umbrella 'Affordable Housing' and get funding from the Affordable Homes Programme.

But, social rent homes are the only homes where rents are linked to local incomes. This makes them the only truly affordable tenure.

By March 2024, the Affordable Homes Programme had so far delivered over 74,000 grant-funded affordable homes, including around 11,000 genuinely affordable social rent homes. That means only 15% of the homes built by the Affordable Homes Programme were the most affordable type of homes. The rest was spent on less affordable tenures like shared ownership and 'affordable rent housing'.

Here's how affordable 'affordable rent' compares to 'social rent':

The new Affordable Homes Programme must prioritise social rent homes.

Lesson three: lack of long-term certainty

The government has already topped up the current Affordable Homes Programme by £0.85 billion and has made available a down payment of £2 billion from the next Affordable Homes Programme.

A key reason given for this was to provide 'long-term certainty' to builders. Homes take a long time to plan, finance and build. So any uncertainty in long-term funding means delays to building.

We can't continue to put money into the Affordable Homes Programme year by year, month by month. To get the homes we need built, we need long-term pledges and consistent funding.

Conclusion

The successor to the current Affordable Homes Programme genuinely could be a turning point for this country. Over the last decade, homelessness numbers have gone up dramatically, private rents have increased, and every day, we hear awful stories of more children growing up in temporary accommodation. We believe that on 11 June, the chancellor has a choice: to do something that would fundamentally transform housing in this country or watch the housing emergency get worse.

Please chancellor, invest in social housing.