Brick by Brick: A Plan to Deliver the Social Homes We Need

A Shelter report by Venus Galarza, Hannah Rich, Charlie Trew, Sam Bloomer, Charlie Berry and William Matthews.

- Part 1, section 1: Executive summary

- Part 1, section 2: Invest in social homes to boost growth

- Part 2, section 1: The bricks to build homes

- Part 2, section 2: Invest in social housing with a redesigned Affordable Homes Programme

- Part 2, section 3: Unlock the land system

- Part 2, section 4: Revitalise and unblock the planning system

- Part 2, section 5: Boost council house to deliver social homes

- Part 2, section 6: Create more ways of delivering new homes

- Part 3: Conclusion

- Endnotes

- Enquiries and Thanks

Part 1, section 1: Executive summary

Millions of families across England live in poor conditions in some of the oldest housing stock in Europe.

Many homes are poorly insulated and are riddled with damp and mould

Renters are forced to choose between feeding their families and paying ever-rising rents, and every three minutes a private renter is served a section 21 ‘no fault’ eviction notice.¹

1.3 million households are on social housing waiting lists, never knowing if they will ever have a decent home.²

145,000 homeless children live in uncertainty, without the stability and security that a home should provide for every family.³

It doesn’t have to be this way: the new government has the power to ensure everyone has a safe, affordable, and secure place to call home.

The only lasting solution to the housing emergency is to build genuinely affordable social rent homes. There is widespread agreement across the political divide and within the housing sector that England needs at least 90,000 social rent homes each year for the next 10 years.

This would be enough to house every homeless household and clear most social housing waiting lists.

Why social rent?

Politicians often talk about social housing and affordable housing in the same breath, but this can distract from what should be the key focus of any government looking to end the housing emergency: social rent. Social rent is the only genuinely affordable tenure as rents are set by a formula linked to local incomes. Tenancies are secure and rent increases are more predictable than in the private rental sector. On average, social rents are a third (33%) of private rents – whereas ‘affordable rents’ are up to 80% of market rents.⁴ People on ‘lower’ incomes – in some places reportedly with salaries as high as £30,000 – can fail affordability checks for Affordable Rent, so it is not truly affordable.⁵

‘Affordable housing’ also refers to homeownership products like shared ownership, where tenants must be able to afford: the deposit (c.5-10% of the share); both rent and mortgage payments; and the cost of repairs. While this can help more affluent households into homeownership, it is not affordable for the 46% (nearly half) of private renters who have no savings at all because rents are so high.⁶

The creation of ‘Affordable Rent’ has worsened the homelessness problem by draining government investment away from social rent – so now there are barely any social rent homes built. Thanks to Right to Buy, in the last 10 years there has been a net loss of 260,000 social rented homes, including 11,700 homes lost last year alone.⁷

This report, therefore, focuses on social rent as it is the tenure most needed to tackle the housing emergency and give people a genuinely affordable and secure home. Ending the housing emergency is a smart investment. There is a clear link between building 90,000 social rent homes and growing the economy. In February 2024, Shelter, in partnership with the National Housing Federation, commissioned research showing that there would be significant economic benefits to building and managing 90,000 social rent homes. The total benefit is estimated to be £51.2 billion over 30 years. The cost of building is balanced out by the economic benefits within only a few years. It pays for itself to the economy in three years and the Exchequer would get its money back in just over a decade.⁸

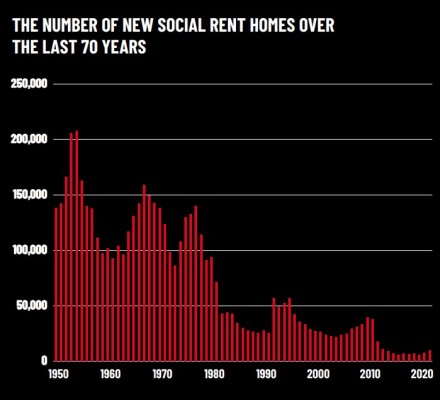

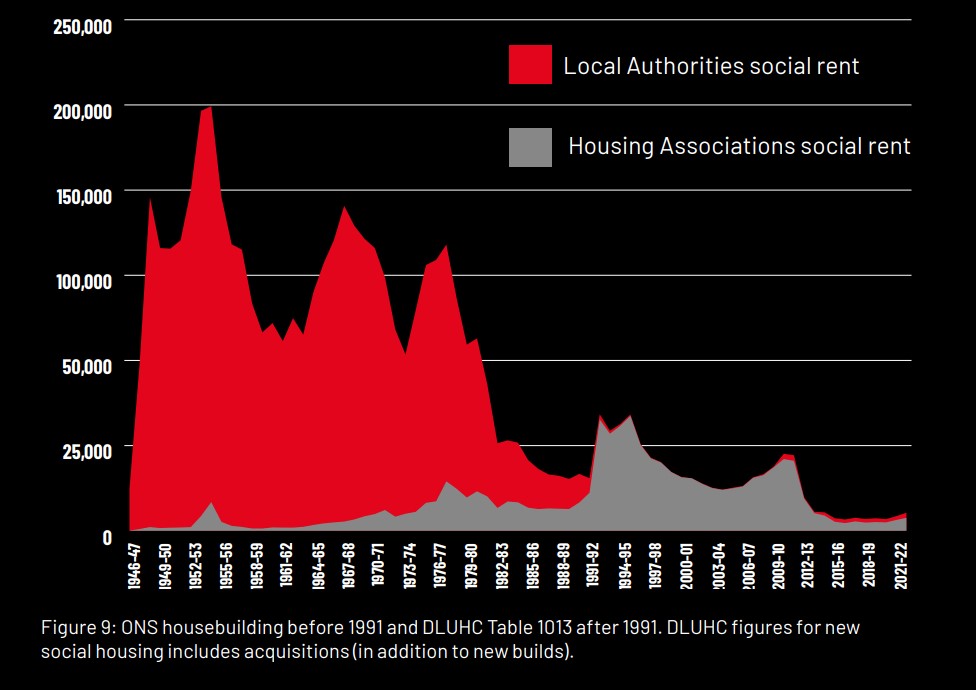

Figure 1 - Source: DLUHC, Table 1000 and ONS, housebuilding

The building bricks: a six-point plan

Set a clear ambition

A new Affordable Homes Programme

Unlock our land system

Unblock our planning system

Boost council building

Create more ways of delivering new homes

1. Set a clear ambition

1. A clear ambition and vision for the housing system is needed. It is critical to increase the overall supply of new homes, but this cannot be achieved without significantly increasing the supply of social rent homes.

The last time this country delivered 300,000 homes a year was 1969 when nearly half of those homes were council-built social homes.⁹ As the total housing supply in England is only at c.234,000 a year,¹⁰ it is likely impossible to deliver 1.5 million homes by the end of the next parliament (i.e. within 5 years) without the government directly getting involved in housebuilding and significantly increasing grant funding for social housing. The last government tried every lever to boost the supply of private homes but failed. A 2024 review by the Competition and Markets Authority concluded that this country failed to build enough homes because of an over-reliance on the speculative development model: where private developers buy land and gamble that by building housing, they can sell parcels of that land at a profit.¹¹

To realise a profit after land and build costs, developers sell new private homes at a premium price, but only a handful of people in a local area can afford them. To keep prices up they must slow build-out and drip-feed the market.¹² The only way to encourage private developers to boost private build-out is to increase the amount people can borrow to pay this premium price. This defeats the purpose of building more homes: as it is impossible to improve affordability with measures designed to sustain house prices. Analysis shows that 300,000 private homes a year will not improve affordability.¹³ Conversely, every social rent home improves affordability for every family housed. It is not enough to have an overall housing target: the new government must also set a clear ambition with a strategy behind it. The consequences of failure are clear: the last government had an overarching target, but it planned to boost private housebuilding in the hope that helping some into homeownership faster would improve affordability overall. This trickle-down housing failed on its own terms. Homeownership is still out of reach and the consequences are clear: sky-high rents, rising evictions and record levels of homelessness.

The new government must set a clear ambition to end the housing emergency (ending homelessness and housing everyone on social housing waitlists) and to improve affordability. To get there, it needs a clear build target - 90,000 social rent homes. Everything else flows from this ambition.

2. Invest in a new, redesigned, Affordable Homes Programme and change fiscal rules to incentivise investment in infrastructure to boost growth

The government’s most direct lever to boost housebuilding is with a new 10-year Affordable Homes Programme to provide grant funding for new social rent homes.

To ramp up to 90,000 we need to see sustained investment and changes to the rules to:

focus funding on social rent as a priority within the overall programme so that the vast majority are for social rent and secure funding for 10 years

boost grant rates to cover more of the cost of a social home and remove ‘cost minimisation policies’ that prioritise maximum units for the cheapest price over social rent

provide a single front-end ‘one-stop shop’ for all housing funding,¹⁴ so housing associations and councils can focus on delivery over navigating bureaucracy

replace competitive, short-term bidding wars with a needs-based formula

allow funding to be used on acquisition and on bringing empty homes into use

devolve powers to regions and Combined Authorities (similar to Greater London Authority powers)

return the approval process to DLUHC from HM Treasury

Moreover, the government needs to take a more mature approach to overall spending targets and review fiscal rules that hold back growth. It must:

design a ‘golden rule’ that enables investment in infrastructure spending to promote growth, and define social housing as infrastructure

consider moving away from Public Sector Net Debt so the Housing Revenue Accounts of stockholding local authorities and Local Housing Companies aren’t included in fiscal rules - in line with the EU, the IMF and most OECD countries

reform HMT appraisals and move beyond narrow Benefit-Cost Ratios (BCRs) which disincentivise investment in social housing

introduce a new long-term rent settlement for housing associations, along with scrapping the benefit cap and bedroom tax to prevent people falling into homelessness

3. Unlock our land system

The cost of land is a major barrier to social housebuilding. This huge cost makes it impossible for councils to deliver genuinely affordable social homes. It also reduces the number of social homes delivered through the planning system. To capture more land value, the government must:

ensure councils can buy land at a fairer price by supporting local authorities to use new rules to eliminate ‘hope value’ and taking forward a test case

reform property taxes to fund social homes and improve tax equality – e.g. abolishing Council Tax and Stamp Duty and replacing them with a Proportional Property Tax

create a comprehensive Land Register to improve land transparency

change land disposal rules so that public land is focused on social rent homes rather than the highest financial return

We need more homes of all types, but we can’t increase overall housebuilding without hugely increasing the supply of social rented homes.

4. Revitalise and unblock our planning system

The planning system should incentivise building genuinely affordable homes and ensure developers pay their fair share. This means the government should:

focus national planning policies (e.g. Local Housing Need) on ending homelessness and clearing social housing waitlists – and use existing 'stick and carrot' measures (e.g. Housing Delivery Test levers) to ensure that local plans are updated to reflect this

fund councils’ planning departments to speed up decision-making and rebalance power between developers and councils

explore planning contracts – where accredited developers get accelerated planning permission in return for meeting set standards and requirements

introduce a duty for local authorities to require onsite delivery of at least 20% social rent on large sites, so they can’t be forced to make concessions

revamp the Brownfield Land Release Fund with a set target of social rent homes on sites released for housing delivery

reverse expansion of Permitted Development Rights, counterbalancing with a clear expectation in the NPPF that quality conversions to residential use should be accepted through the planning system

abandon the Infrastructure Levy and instead strengthen requirements on developers as set out above

5. Boost council building to deliver social homes

Direct delivery by councils has been central to England hitting high housing targets in the past. Unleashing them again could help to build 34,000 social rented homes annually.¹⁵ This could be achieved by:

suspending Right to Buy until net 900,000 social rent homes are delivered and replacing it with a mortgage deposit scheme to help social tenants buy a private home

providing funding for new in-house planning and housing delivery teams/corporations, and funding to upskill them, including a centralised super squad to clear planning application backlogs and set up council delivery bodies across the country

adopting a new national land strategy to better understand what land is available and maximise the delivery of homes on grey belt and brownfield sites

supporting more low-cost council borrowing (e.g. through changes to the Public Works Loan Board)

introducing a central government programme that would support councils to pool resources and expertise

adopting a new Social Housing Contractor Framework to set parameters around rates and pricing each year, providing certainty and confidence in long-term planning and giving councils access to prequalified suppliers.

6. Create more ways of delivering new homes

The government must unlock more delivery vehicles to ensure that every lever is pulled to get more social rent homes. This means the government should:

target support to convert long-term empty homes into social housing as set out in Shelter’s Home Again report earlier in 2024.¹⁶

support community land trusts to deliver over 7,600 social homes per year

use net-zero goals to build social homes for the future which promote climate justice and growth through new-build retrofitting and responsible change of use through the planning system

lay the groundwork for an era of new towns, including the formation of more Development Corporations and the use of land value capture mechanisms

adopt a new model and legislative framework to increase the planning powers of development corporations

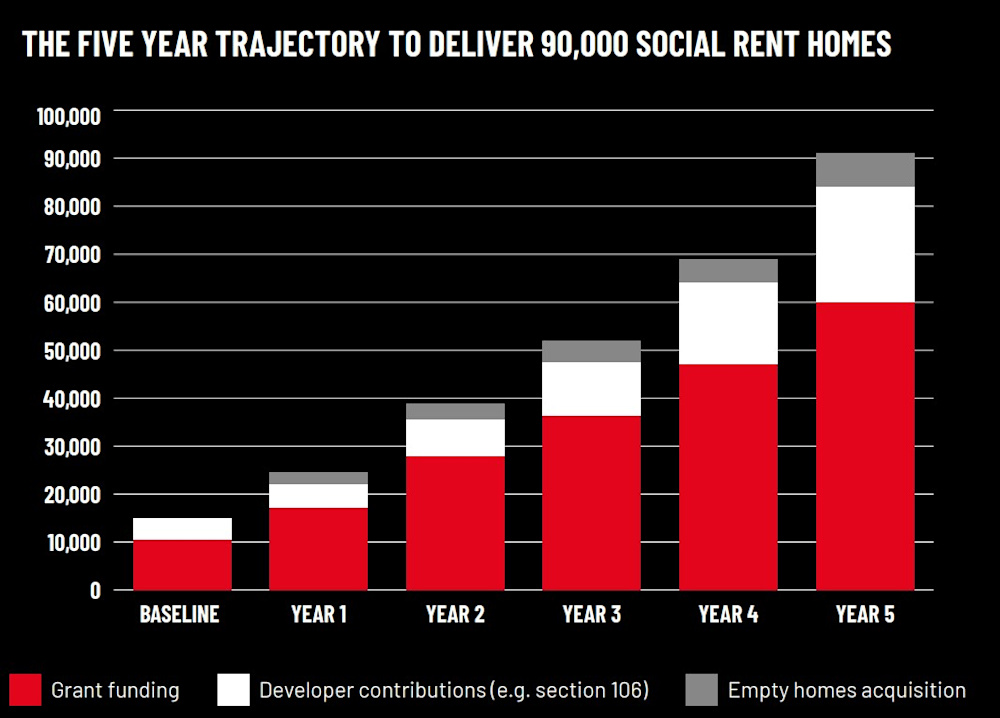

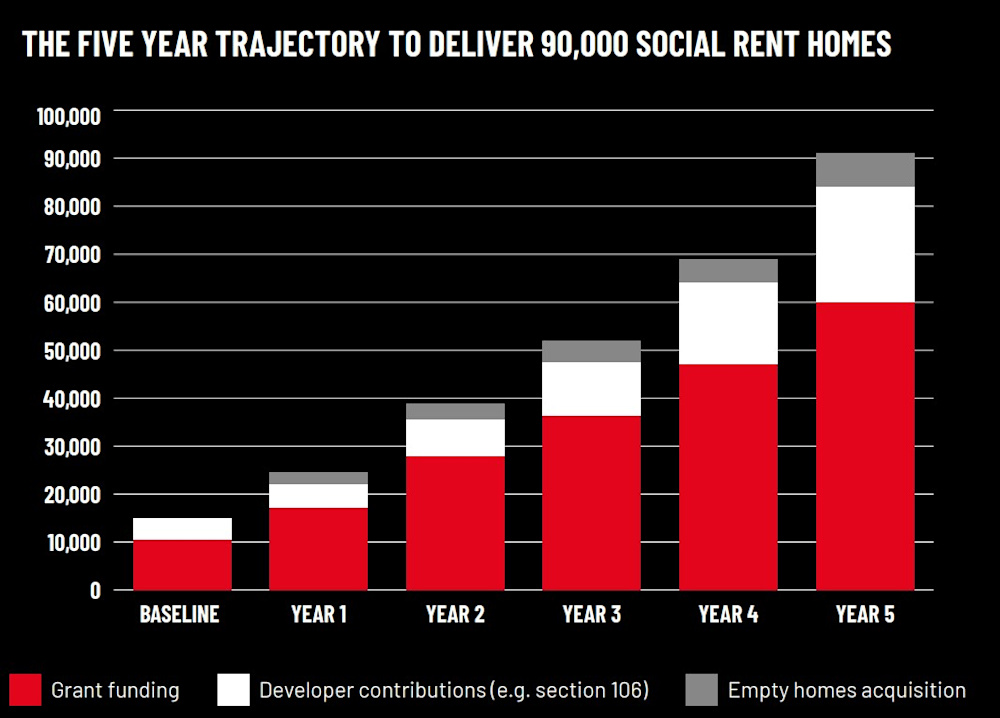

Shelter’s plan can deliver 90,000 social rent homes per year

The government needs a comprehensive plan to deliver the social and economic benefits of a mass-scale building program of social rent homes. Shelter’s plan outlines the key policy and funding interventions needed to reach this target. Grant funding, developer contributions and an empty homes programme could scale up over five years to deliver 90,000 social rented homes per year (see Table 1). We see councils as playing a key role in achieving this social housing revolution with council direct delivery accounting for 34,000 social rent homes, including 4,000 homes delivered due to changes to ‘hope value’.

| Section of the report | Measure or Provider | Number of homes per year |

|---|---|---|

| Invest in a new, redesigned Affordable Homes Programme and change fiscal rules to incentivise growth investment | Grant funding | 60,000 |

| Unlock our Land System | ‘Hope Value’ | 4,000 |

| Revitalise and unblock our planning system | Developer contributions | 24,000 |

| Boost council building to deliver social homes | Council direct delivery | 34,000 |

| Create more ways of delivering new homes | Empty homes | 7,100 |

| Create more ways of delivering new homes | Community land trusts | 7,600 |

Table 1: The number of social rented homes delivered per year by different measures and providers. Note: The table does not add up to 90,000 social rented homes because it includes a combination of measures and providers. The number of social rented homes delivered through grant funding, developer contributions and empty homes sums up to 91,100 social rented homes. The 34,000 council homes are delivered through a combination of grant funding, developer contributions, ‘hope value’ and empty homes. The CLT homes are delivered using grant funding and developer contributions.

While it will be challenging, the government could deliver 90,000 social rented homes per year by the end of the parliamentary term. The trajectory is based on recent trends, historical data and the assumption that a series of policy interventions need to be implemented urgently to achieve this ambitious target.

Figure 2: Our proposed trajectory to ramp up to 90,000 social rent homes in five years, with a key focus on increasing grant funding and developer contributions. Source: Shelter analysis of data and findings from DLUHC, Cebr and Arup.

Part 1, section 2: Invest in social homes to boost growth

England’s broken housing system is a major barrier to growth. People cannot save when they must spend a huge proportion of their income on their rent.

When people can’t afford a sharp rent hike or are pushed further and further away from their jobs, schools, friends and support networks, this not only has an effect on their mental health, but also limits individual productivity and prospects.

People cannot realise their full potential if they’re kept awake at night worrying about the eviction notice that could land on their doorstep at any time, or by their kids coughing because of the damp and mould on the walls of their homes.

Workers can’t perform their best if they must travel hours and hours before they clock in, or if they don’t have a home to go back to.

Schoolchildren will suffer academically if they’re forced to revise for their GCSEs on the toilet because there’s not enough space to do their homework anywhere else.

Every day, Shelter’s frontline advisers hear how the housing emergency is holding people back and ruining lives. High housing costs are the biggest tax on people's potential and housing insecurity robs millions of their future.

A social housebuilding programme would not just end homelessness, transform the lives of millions, and give people the stable, affordable, and decent homes they need. It would also have huge economic benefits, provide stability and lead to growth.

Building 90,000 social rent homes a year would pay for itself in 3 years and add £51.2bn in benefits to the economy over the next 30 years, according to new research by the Centre for Economics and Business Research (Cebr).¹⁷

The report finds that one year of building 90,000 social rented homes would deliver:

£4.5bn savings on housing benefit - as private tenants move into social rented homes where rents are on average a third (33%) of private rents.¹⁸

£2.5bn income from construction taxes - due to increased building

£3.8bn income from employment taxes - as more people are employed to build and manage social housing

£5.2bn savings to the NHS – as people move out of terrible temporary accommodation and homes that harm their health into quality social homes

£4.5bn savings from reduction in homelessness – as people move out of expensive temporary accommodation into permanent social homes

£3.3bn savings to Universal Credit – as people claim less to pay lower rents

Social housebuilding boosts employment in the housing sector

A social housebuilding revolution would create jobs in the construction and wider housing industry. Building 90,000 social rented homes would directly support nearly 140,000 jobs in the first year. Within just three years, the economic benefits of building these homes would fully cover the cost of construction, returning an impressive £37.8bn back to the economy, largely by boosting the construction industry. In the longer term, the construction and management of the homes would return £48.2bn to the economy and government over 30 years.¹⁹

Short-term policy has driven up housing costs and the benefits/homelessness bill

About 30 years ago, then housing minister Sir George Young proclaimed that housing benefit would ‘take the strain’ for rising rents, as the government privatised housing association finance, lowered grants and deregulated the private rented sector. This signalled the beginning of a new era of housing policy where ministers would rely on the private market rather than invest in social housing.

Fast forward to today, a third of private renters now spend half or more of their income on rent²⁰ and rents are at their highest level since records began and rising faster than ever.²¹ This leaves struggling families forced to choose between feeding their family and keeping a roof over their heads. There are more than 145,000 children homeless in expensive temporary accommodation (TA).²² George Young’s claim that ''there can be no question of people losing their homes because they cannot afford to pay'' has been proved wrong.²³

With cuts to the social housing budget and millions of social homes sold off, the private rented sector (PRS) has doubled in size in the last 20 years,²⁴ as more low-income renters are forced to compete for some of the worst homes in the country.²⁵

With rising rents, nearly half of private renters (46%) now have no savings²⁶ – many are just one unexpected bill away from homelessness. A third (32%) are reliant on housing benefit to pay their rent.²⁷ This means that, in reality, the government is now subsidising private landlords’ second homes or property empires.

Social housing investment creates savings on the benefit bill

Unlike other infrastructure projects like roads, social residents pay rent, so there is a return on investment. Lower rents can mean a lower benefit bill. Research by Cebr shows that just one year of building 90,000 social rented homes would save nearly £250m per year on the housing benefit budget, or £4.5bn in total, as households paying private rents move into social homes.²⁸

Did you know?

Most landlords (55%) have no mortgage on any of the homes that they let out.²⁹

Nearly £12bn is spent a year subsidising private rents.³⁰

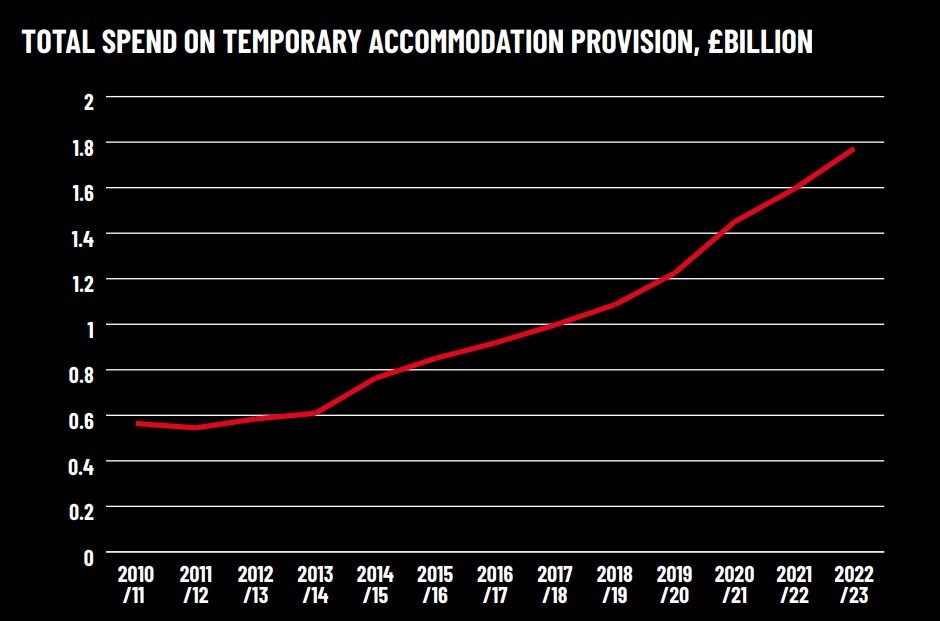

£1.7bn was spent on temporary accommodation last year.³¹

In the PRS, housing benefit flows from central government through tenants and into the hands of private landlords. While critical to preventing homelessness, this money is ‘lost’ to the public for good. By contrast, in the social housing sector, housing benefit payments are reinvested: cash flows through tenants to social landlords (councils or housing associations). In this instance, this money is either spent maintaining the existing stock or invested in building more social housing – providing long-term value to the public.

Because the government also controls social rent levels, if more people who need housing benefit are in social rented homes, the government could more effectively control housing benefit spend, rather than watch it spiral out of control.

Pen profile

Scenario A:

This is Jodie. Jodie’s rent for a 2-bed flat in Birmingham is £200 a week. She’s only able to claim £172 housing benefit a week, so she’s got a shortfall of £28 every week which she can’t afford. She’s already renting one of the cheapest homes in the area, so she’s worried that she’s going to become homeless. She’s been struggling to cope with essential costs each month and has cut down on meals and turned off the heating. Her landlord is using the rent as seed money to buy up more properties in the area – pushing homeownership out of reach for local people and causing rising rents.

Scenario B:

Jodie moves into social housing, where her rent is now £99 a week. She now claims £73 less housing benefit than before, but it now covers the whole cost of her rent. Jodie can now afford all the essentials, buy a new school uniform to replace the one that was getting too small for her daughter and maybe even start a rainy-day fund. Her rent goes to the council, who use it to build more social housing, bringing down the cost of renting for everyone.

Figure 3 - Department of Work & Pensions (DWP) benefit expenditure and caseloads tables. *Data for 1989/90 includes housing benefit spending for housing association tenants as well as private renters.

Figure 4 - This graph shows that there has been a significant upward trend in the amount of money spent on temporary accommodation since 2010-11, with a record high of £1.7 billion spent between 2022-23. Source: DLUHC, Revenue outturn housing services.

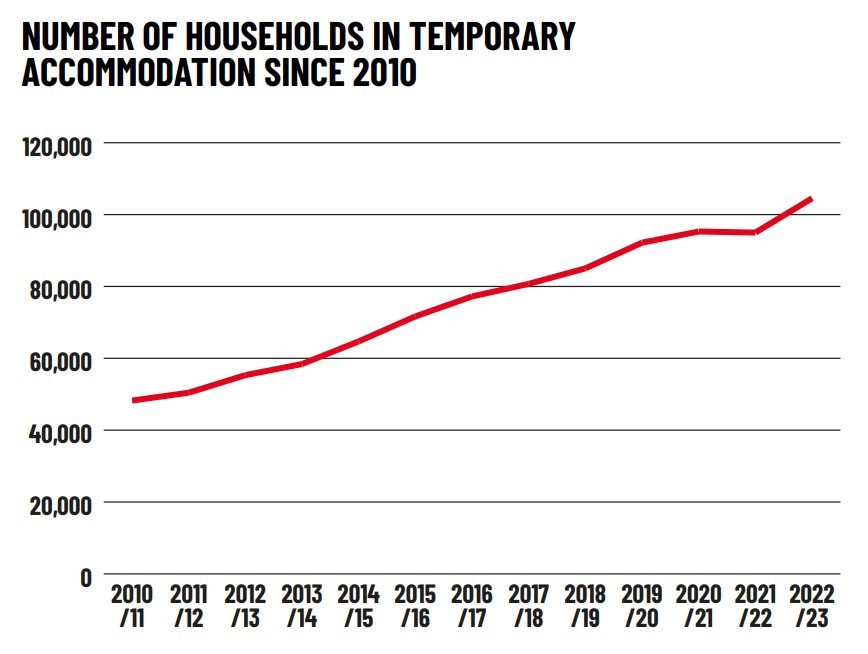

Social housing investment creates savings on homelessness accommodation

The lack of social housing means that homelessness has more than doubled since 2010 and spending on temporary accommodation has increased by a staggering 62% over the last five years.³² Cynical private companies seeking to profit from councils' desperation make millions by charging nightly rates for temporary accommodation.³³ Faced with a rising tide of homelessness and no social housing, many councils are now on the brink of bankruptcy paying for terrible temporary accommodation and fearing they will have to issue a Section 114 notice either this year or next.³⁴

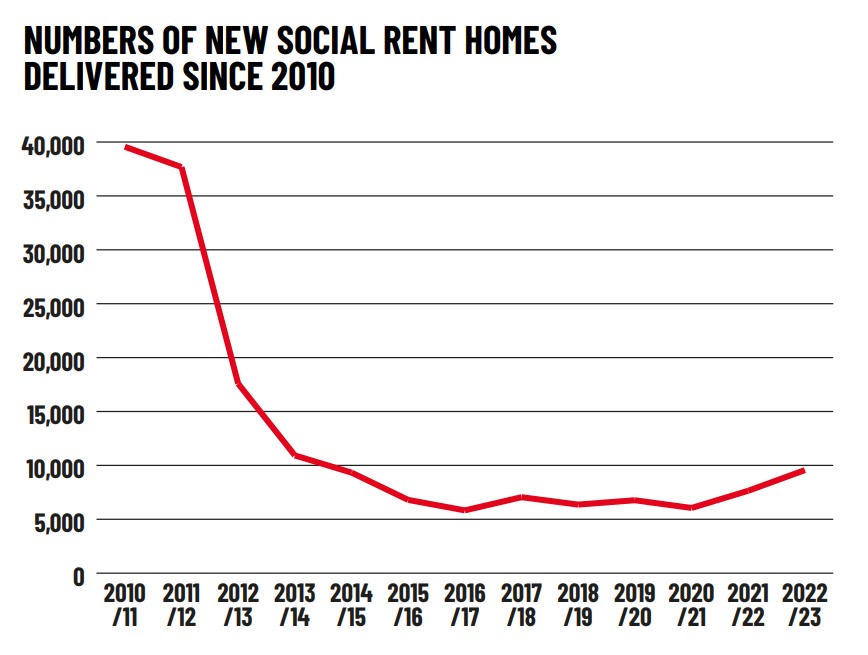

Figure 5 - Source: New social housing - DLUHC, Live tables on affordable housing supply, Table 1000

Figure 6 - Source: Households in TA: DLUHC, Statutory homelessness statistics, Table TA1

Building just one set of 90,000 social homes would save councils £245m a year on homelessness services – 10% of total spending last year – and result in £4.5bn in savings over the next 30 years, over and above the housing benefit savings.³⁵

Social housing can improve health outcomes and save money for the NHS

Building 90,000 new social rent homes could save the NHS £5.2 billion and would lead to a substantial reduction in annual health services usage of £1,914 per household.³⁶

Being homeless on the street can be lethal. In 2021 (latest available ONS statistics) an estimated 741 people who were street homeless or in emergency accommodation died in England and Wales - 54% higher than when records began in 2013. This equates to two people dying every day. The average age at death was 45 for men and 43 for women – more than 30 years lower than the average age at death of the general population.³⁷

Being homeless and living in temporary accommodation puts children’s lives at risk. Between 2019 and 2023, homelessness and TA contributed to 55 children’s deaths.³⁸ Unsanitary or unsafe conditions – rooms caked in damp and mould, infested with rats and cockroaches – can exacerbate underlying health conditions like asthma and contribute to children’s deaths.

People in temporary accommodation tell Shelter advisers that they live in constant fear - never knowing when they might next be moved on, sometimes hundreds of miles away from their support network, work or schools. This can have a huge impact on people’s mental health and on their ability to work. Two-thirds (66%) of people living in TA report that their physical or mental health has been damaged by their living situation.³⁹

The insecurity of private renting – worrying about facing a large rent hike or being evicted for no good reason – takes a toll on renters’ mental health. Almost half of private renters (46%) say that worrying about how they will pay rent is making them feel anxious and depressed.⁴⁰ This can make it harder for people to concentrate at work.⁴¹

Under the constant threat of section 21 'no-fault' evictions, private renters are left feeling scared to complain about the dangerous and unhealthy conditions in which they live. More than half a million private rented homes in England (579,000) have hazards that are so dangerous they are assessed as ‘a serious and immediate risk to a person’s health and safety’.⁴² One million private rented homes are categorised as being in disrepair: containing hazards, and/or failing to provide efficient insulation and heating or modern facilities, such as a suitable bathroom or toilet.⁴³

Poor housing conditions cost the NHS England a staggering £1.4 billion a year – putting a massive strain on services.⁴⁴ Children living in bad housing are twice as likely to suffer from poor health than those living in good housing and children living in cold homes are twice as likely to suffer from respiratory problems than those living in warm ones.⁴⁵ Damp and cold conditions cause and exacerbate lung diseases, and all lung conditions cost the NHS £11 billion annually.⁴⁶ Respiratory incidences and mortality rates are higher in disadvantaged groups and underserved communities. The NHS emphasises that the equality gap is widening and leading to worse health outcomes with poor housing being one of the main determinants of this.⁴⁷

Social housing has the lowest proportion of non-decent homes and health hazards of any other tenure.⁴⁸ This is why we need more decent, genuinely affordable social homes.

Social housing can boost productivity and result in better education outcomes

Half of teachers (49%) report working with children who are homeless or who have become homeless in the last year.⁴⁹ This can inflict immense damage on children’s education. For instance, a shocking 91% of teachers say children are coming to school tired as a result, while 86% say it’s caused children to miss school.⁵⁰

Shelter services have heard from homeless kids forced to do their GCSE homework on

the toilet, as there’s no space in their homeless accommodation - exams which can have a life-changing impact. In Shelter’s previous report, Still Living in Limbo: Why the Use of Temporary Accommodation Must End, one parent highlighted that their child sleeps in school because they must wake up very early to start their long commute⁵¹. Another person pointed out the impact on education:

"Even if they’re in school it’s not just the missed days if they’re exhausted, it’s not just being present, it's being able to learn." ⁵²

Constant moves in the private rented sector can disrupt children's education – as they are forced to switch schools and move away from their friends and family because parents can no longer afford to stay in their area. This can negatively impact the course of a child’s life.

Poor or unstable housing leads to lower economic contributions, increased crime, and greater reliance on public services. Cebr estimates that building 90,000 new social homes would reduce disruption to education and lead to overall savings of £2.7bn.

Social housing investment is 'recession-busting' and 'countercyclical'

In uncertain economic times, some developers scale back building. High interest rates suppress demand for private new builds which come with a premium price tag. The cost of retrofitting and remediation diverts cash from new building. If builders slow build out, this can lower demand for builders, architects, etc - even as prices remain stubbornly high.

Private housebuilding is cyclical: demand for private sale (or affordable homeownership products) goes up and down with the wider economy as house prices wax and wane.

But investment - specifically in social rent homes - is 'countercyclical'. Demand is insatiable so you can always rent it out, and investment protects capacity in the building system. Because other “affordable” products are heavily tied to the private market, they are not ‘recession-busting’.

Meanwhile, more social rent homes would help reduce the burden on councils whose budgets are going to be under stretch from increasing homelessness and demand for their services in times of economic need. Limited investment can also keep private developers afloat. By investing top-up funding to convert planned private homes into social rent, developers can keep building: protecting jobs and capacity.

Social rent is the key to unlocking growth across the country, and to building more resilient and stable communities that can weather financial storms.

Part 2, section 1: The bricks to build homes

1. Set a clear ambition

It is not possible to increase overall housebuilding without significantly increasing the supply of social rented homes.

The last time this country delivered 300,000 homes a year was in 1969 when nearly half of the homes were council-built social homes.⁵⁴ Today, net housing delivery stands at c. 234,000.⁵⁵

Delivering 1.5 million homes within five years (i.e. by the end of the next parliament) will likely be impossible without the government building social rent homes and increasing grant funding. Given tough economic conditions, and stubbornly high interest rates, the only way to bridge the c.66,000 homes a year gap within this timeframe, will be to boost social rent delivery significantly.

The reason we have failed to build enough homes is an over-reliance on the speculative development model: where private developers buy land and gamble that by building housing they can sell parcels of that land at a profit.

For the developer to realise this profit, the housing must be sold at a premium because they need to cover the build cost and the price they paid for the land. There are usually only a limited number of people in the local area that can afford to buy at this price, despite there being many people who need a home but are priced out - this is what developers call ‘low demand’. This incentivises developers to slow build and drip feed homes onto the market to maintain high house prices and protect their profit margin - as highlighted in the Letwin review and by the Competition and Markets Authorities’ report.⁵⁶,⁵⁷

The only way to encourage private developers to boost private build out, therefore, is to boost demand for homes at premium ‘new-build’ prices: increasing the amount that people can borrow so that they can afford to pay more for a home or helping developers source wealthier customers overseas. This defeats the purpose of building more homes: it is impossible to improve affordability with measures designed to sustain house prices. There is little point in increasing housebuilding up to 300,000 homes a year if they are all market homes: analyses show that this target number of private homes would not improve affordability.⁵⁸

To start to make a dent, this target would likely need to be significantly increased and private developers would need to be convinced to work against the interest of their shareholders/investors to drive down the value of their product. This is why ‘trickle-down housing’ has failed even by its own goal to boost homeownership.

Conversely, social rented homes directly improve affordability for those that rent them, and as there is nearly unlimited demand for social rent there is no need to drip feed.

Many commentators claim that all we need to do is to increase the number of private homes by removing planning restrictions. While planning delays need to be addressed, the evidence is clear: it is not possible to improve affordability or unlock growth solely by enabling private developers to build whatever they want, wherever they want it. Social housing must be a fundamental and significant part of the equation.

Others note that increasing overall supply delivers more social rented homes through Section 106 developer contributions. While this is true to an extent, developers will seek to minimise contributions: barely 3,500 social rented homes were delivered using developer contributions last year (2022/23) as developers focused on ‘affordable’ products or wriggled out of commitments.⁵⁹ This means that the government needs to take measures to secure more social rent homes from developers – and see the purpose of increasing overall housebuilding as a way to secure more social housing, rather than as an end in itself.

The last government set an overarching target but with no clear purpose beyond helping people into homeownership. The consequences were dire: sky-high rents, record levels of homelessness and many families closer to homelessness than homeownership. Alongside a wider target, the government must commit to building 90,000 social rented homes every year.

We need a fundamental rethink of the housing delivery model and to stop relying on speculative development as the only way to get new homes. This is why the government needs to set out a clear ambition to end homelessness and clear waitlists, or the housing emergency will continue to worsen. Everything flows from this central ambition.

Part 2, section 2: Invest in social housing with a redesigned Affordable Homes Programme

The government’s most direct lever to increase social housebuilding is grant funding through the Affordable Homes Programme (AHP). The government should deliver a new, reformed, 10-year Affordable Homes Programme that is focused on the delivery of social rent over other tenures. Alongside this, it should commit to a long-term rent settlement so social housing providers and tenants have the confidence and security to plan for the future. There is no way to solve the housing emergency without this investment.

A redesigned Affordable Homes Programme

Improve grant rates and social rent focus

Social housing grant only covers a percentage of the cost of building a social home, so providers must make up the shortfall with other funds. They borrow against future rental income (money otherwise earmarked for maintenance) and must ‘cross-subsidise’ to build and sell private homes to the highest bidder. This makes social rent less viable. Anecdotally, a social rented home can be delivered in London in the current programme for c.£180,000 grant per unit (far less outside London).⁶⁰ Recent Cebr analysis assumed a higher average grant rate of almost £170,000 across England - with grant funding increasing to over £252,000 per home in London.⁶¹

Reform cost-minimisation rules

While social rent is now ‘a priority’ in the Affordable Homes Programme, and the £50 rule has been scrapped in the latest guidance, the current programme still uses ‘cost minimisation’ to assess bids made by councils and housing associations for grants.⁶² This prioritises bids that deliver the most homes with the least amount of money – the lowest ‘grant rate’. Other tenures like Affordable Rent, Shared Ownership or First Homes, require much lower grant rates than social rent. As a result, ‘cost minimisation’ makes it extremely hard to get the funding needed to build good quality, genuinely affordable social housing.

Commit to longer-term funding cycles

Large housing projects can take 5-10 years to plan and complete, but historical funding has only lasted 5 years. Recent UCL research shows that a 10-year programme would give developers certainty to build more, faster and would encourage housing associations to:⁶³

buy land without planning permission, hugely decreasing the cost of development and resulting in more homes built

take on a wider range of sites, including larger sites - boosting supply

build stronger long-term partnerships with local authorities and private developers to take on larger, more complex sites

hire more staff (eg. in land acquisition) to make better land purchases, faster - and for councils apprehensive about setting up housing delivery arms after years of divestment, a 10-year programme and ambitious social rent targets would send a strong message to get them back into housebuilding

have a single ‘front end’ for all housing investment, including net-zero funding. Housing development is complex: a single project may require transport, retrofit, brownfield and levelling up funding just to get off the ground. Today, this means housing associations and councils must write separate bids for each pot and change overall plans to fit a complex web of funding requirements. Instead of having to adapt to government working, social housing developers should only have to apply to a single location with a single application - leaving the process of identifying ‘where’ the funding comes from up to civil servants, within a specified Service Level Agreement timeframe.

replace competitive, short-term pots with a needs-based formula as recommended by On Place.⁶⁴

flex rules so that Affordable Homes Programme funding can be used to acquire and bring back into use empty homes, or retrofit where net additionality rules are less relevant.

Change fiscal rules to support social housing and incentivise investment in growth

We need investment to fuel our economic machine, but despite total investment in the UK being significantly behind our nearest G7 competitor, most parties are continuing with plans to make further cuts to government investment, according to the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR).⁶⁵ The Housing and Local Government department has seen particularly harsh cuts since 2010.⁶⁶

This policy of cuts and no replacement investment has resulted in years of sluggish growth and stubbornly low productivity. This failure to invest in the infrastructure which unlocks growth is driven by government policy. Different governments have held themselves to self-imposed (and often poorly designed) rules that drive short-term cuts and disincentivise long and medium-term investment. In particular, the obsession with short-term debt targets and announcement-driven fiscal moments means the government has focused on cuts over long-term investment.

Even the accounting methods that the government uses to measure growth, productivity and relative value of investments, can in some cases disincentivise investment. For example, the Treasury Green Book net benefit guidance explicitly excludes the macroeconomic effects of government spending on employment and productivity, because it’s hard to make an objective comparison between two projects.⁶⁷ Meanwhile, an increase in land values is used as a proxy for measuring growth in the benefit-cost ratio measurement (BCR). By design, social housing investment should result in lower land values than private development, so this comparative measure makes little sense.

Perhaps more damaging is the culture these rules create across Whitehall, as civil servants internalise these accounting measures in their decision-making: saving money is more important than building resilience or driving growth.

Others (eg. On Place), have written more extensively on what fiscal rules need changing. Shelter supports certain measures, including:

designing a ‘golden rule’ that enables investment in infrastructure outside of the debt reduction rules, to prompt long-term growth and cut costs long-term⁶⁸

defining housing investment (specifically sub-market social housing) as infrastructure investment for the purposes of this rule.⁶⁹

considering using General Government Gross Debt (which excludes public corporations and is used by the EU, the IMF and most OECD countries), rather than Public Sector Net Debt - which includes the entire Housing Revenue Accounts of stockholding local authorities as well as Local Housing Companies and ALMOs - for fiscal targeting.⁷⁰

reforming HMT appraisals and moving beyond narrow Benefit-Cost Ratios (BCRs) - so that housing projects are measured against their socioeconomic impact/value, rather than crude ‘value’ assessments like land value uplift.

Boosting housing associations’ financial capacity: long term rents and cheaper debt

Lack of grants means housing associations (HAs) have had to cross-subsidise (building private homes for sale) and borrow heavily to fund development. Recent interest rate rises drove up debt costs so that many have hit their debt ceiling faster. Higher costs combined with major safety and quality problems, have meant that large providers have had to switch investment to existing stock. Despite this, while councils gear up to build, housing associations are in pole position to deliver if the right interventions are made to overcome these challenges: they have the structures, people and experience to build, but they need measures to boost their financial capacity.

More generous grant rates and tweaks to the Affordable Homes Programme will reduce debt reliance and help ease the pressure, directly stimulating building. Providers also need cheaper debt, so the government should take measures to drive down the cost of debt (e.g. extending debt guarantees to all new debt).

The lack of certainty about future rents makes it hard to plan. However, the government must balance this against the impact on tenants and the risk of increasing homelessness so, to reach a settlement, two punitive measures must first be scrapped:

the Benefit Cap limits the maximum amount of benefits that working-age households can claim to £1,835 per month outside London or £2,110 inside London, regardless of the size of home they need, or the number of children they have. A sharp rent increase will result in more families hitting the benefit cap, pushing them into arrears and towards homelessness. Families in temporary accommodation will fail affordability checks for the social tenancies they need to escape homelessness. In 2022/23 there were already 22 areas in England where average council rents were unaffordable for benefit capped households.⁷¹

Pen profile

Example 1:

Fatema is a lone parent with three children living in social housing. She cannot work because she is caring for her youngest child who is under school age, so she receives universal credit but is subject to the benefit cap. If Fatema’s rent increases, her benefits income will not go up, so she will have to cut back on other essentials.

the Bedroom Tax limits housing benefit for working-age social tenants classed as having a ‘spare bedroom' based on their household size. If rents rise, people already hit by the Bedroom Tax will have a bigger shortfall between their income and their rent, which could result in homelessness. 373,000 social renters (12%) receiving Universal Credit or legacy housing benefit are affected.⁷² Affected households lose 14% or more of their housing benefit entitlement depending on the number of spare rooms they are deemed to have. Downsizing is rarely an option due to the shortage of suitable social homes and because affected households may have strong reasons for needing an additional bedroom, but are not eligible for an exemption.

Pen profile

Example 2:

Gary lives in a 2-bed home that he rents from a housing association. Gary’s work is insecure, and his income fluctuates month-to-month, so he claims Universal Credit. Gary‘s daughter from a previous relationship stays with him at weekends, so he can’t downsize. Despite this, Gary is affected by the Bedroom Tax and the housing element of his Universal Credit is reduced by 14% as a result. Gary already struggles, so a further increase in his rent would be unmanageable.

More generally, changes to the rent settlement must ensure that rents remain genuinely affordable. This likely means maximum caps on rent increases. This is why we recommend that the next government sets up a Social Rent Commission to review the current rent settlement and give binding recommendations.

Increasing investment in social rent homes is critical to boost social homebuilding

Increasing grant funding for social rent homes, fixing our fiscal rules and implementing a long-term rent settlement are central to reaching the target of 90,000 social rent homes per year after five years. Shelter estimates that two-thirds of the 90,000 homes would be grant-funded (60,000). Cebr estimated that constructing 60,000 social rent homes would require £11.8 billion in grant funding.⁷³ More work is planned to understand the full cost of a renewed AHP which prioritises homes for social rent and also considers other tenures including Affordable Rent and Shared Ownership.

The last time this country delivered close to 60,000 grant-funded social rent homes was in the early 1990s.⁷⁴ Since then, there have been a series of policy changes that have seen funding deprioritised away from social rent towards other ‘affordable homes’, including Affordable Rent and Shared Ownership products.

Ramping up to 60,000 grant-funded social rent homes per year in five years is ambitious but achievable. Last year around 4,000 social rent homes were delivered using grant funding.⁷⁵ We assume that delivery could increase at the same rate as the last two years (63% increase) until year two.⁷⁶ This is a reasonable assumption as the number of grant-funded social rent starts on site continues to increase across England, with a doubling of starts in London in the last year.⁷⁷ We assume a slower rate of increase (27-30%) in years three, four and five, reaching 60,000 homes in year five (see Figure 7).⁷⁸

Figure 7 - Shelter’s trajectory to ramping up to 90,000 social rent homes in five years with a focus on increasing grant funding and developer contributions. Source: Shelter analysis of data and findings from DLUHC, Cebr and Arup.

Part 2, section 3: Unlock the land system

The cost of land is a major barrier to building social homes in England

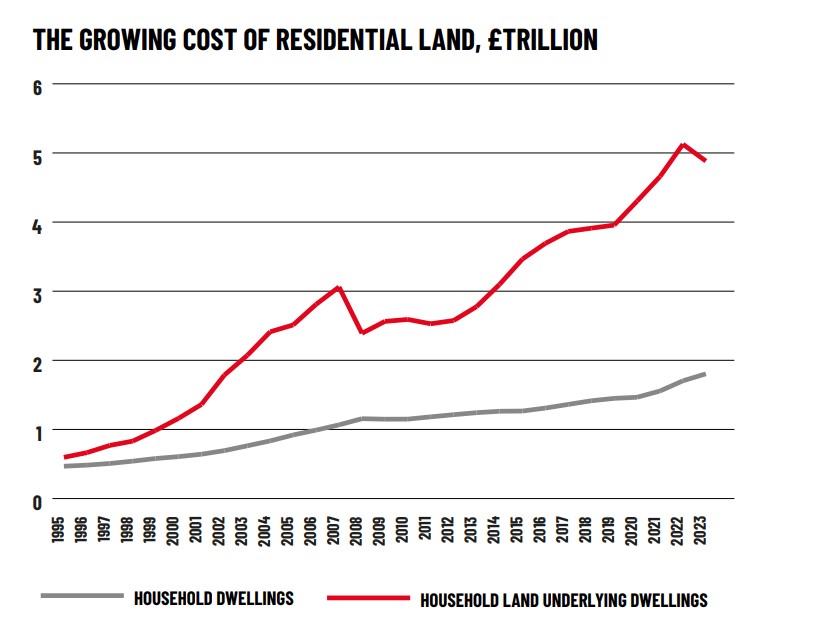

The staggering growth in land and property prices in recent decades has fuelled the housing emergency, as homes have become less and less affordable. As well as driving up rents, increasing land values have also driven up the cost of development.

In 2023, the cost of land had risen to over 70% of the price paid for a new-build home, according to ONS figures.⁷⁹ The cost of residential land has continued to increase and in 2023, was valued at £4.9 trillion (over two-fifths of the UK’s total net worth).⁸⁰ The price of land directly reduces the amount of social housing that councils, housing associations and private developers can build.

Figure 8 - Source: National balance sheet from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2023

What’s wrong with our land system?

A core principle of an efficient economy is that investment should go towards productive activities, which add value to the economy (e.g. employment), unlock further investment, or address social inequality. Any government seeking to improve the economy should therefore root out ‘rent-seeking’ behaviour: when those with wealth use their resources to increase the ‘rent’ (economic return) from an asset without contributing to its productive capacity, making the system more inefficient and unequal.⁸¹ In the land system, this manifests as:

investors buying up land to ‘bank it’ (artificially driving up the price by withholding it from those that would build)

speculators buying sites/parcels, securing planning permission and selling it on at a profit, with no intention to build⁸²

landowners refusing to sell at a fair price, convinced they could secure more profit (even if the scheme could not go ahead at that price)

This rent-seeking drives further economically inefficient behaviour, such as:

developers buying up land in high-demand areas and building only top-price investment flats (restricting land for more affordable tenures that have greater social value, thus limiting further economic activity, eg. nurses and teachers being able to get to work and fuelling local land prices)⁸³

developers building leasehold houses with excessive ground rents (maximising return for no further productivity)⁸⁴

We need to capture land value uplift to build social homes

Land value uplift is the increase in the price of land that happens when planning permission for residential use is granted. Residential land values are up to 93 times higher than agricultural or industrial land so when the government grants planning permission, it effectively gifts the landowner millions of pounds for doing nothing.⁸⁵

Land value capture (LVC) measures aim for the government or community to get some of the ‘uplift’ in value, to use on socially or economically useful projects (like social homes).⁸⁶ LVC mechanisms can also discourage ‘rent-seeking’ behaviour by changing landowners’ expectations of what a ‘fair price’ is.⁸⁷

There are many forms of LVC, including Section 106 affordable housing contributions and the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL), in which councils require homes or funding from developers in return for planning permission.⁸⁸ These are imperfect mechanisms that need to be improved to capture greater value (see the planning section). Other measures include removing ‘hope value’ for compulsory purchase and a land value/property tax (see overleaf). Badly conceived or implemented planning reform can incentivise rent-seeking behaviour: for example, owners of brownfield land knew that they could only expect existing use value when selling. But recent changes to permitted development rights,⁸⁹ and the government’s ‘brownfield-only’ approach, could increase the price that landowners expect when selling and may have unwittingly driven up land prices. Evidence suggests that political focus on brownfield sites has actually driven up land values and in turn, created a less efficient land system.⁹⁰

Support councils to use ’hope value’ rules to help build social homes

A major barrier to social housebuilding is ‘hope value’, a 1961 rule that forced local authorities to pay a high premium for land when using Compulsory Purchase Orders (CPOs) - as if they were building luxury homes. This made it impossible for councils to negotiate on land purchases. Civitas estimated that the removal of ‘hope value’ could slash 38% off the total development costs of a mass-scale building programme.⁹¹

There is now a clear avenue to remove ‘hope value’ for development that serves the public interest - like a school, GP surgery or social home. Through the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act, when negotiations with landowners fail (and as a last resort), local authorities can now apply to the Secretary of State to get ‘hope value’ removed when using CPOs to buy land in the public interest.⁹² If approved, the local authority will pay a fairer price for land, as it would be at, or closer to, the existing use value.

Recent analysis by Arup - a global engineering, planning and sustainable development firm - suggests that an increase in the use of the new CPO powers could lead to an additional 4,000 social rent homes per year by 2029/30. Even with this conservative estimate, this would be equal to over two-fifths (42%) of the total social rent homes delivered last year alone.⁹³ With the right interventions to support councils, the number is likely to be higher if properly backed by central government and with further CPO reform aimed at social housing delivery. Allowing councils and development corporations to pay for land at existing use value, as set out below, will also help with any future plans for new towns.

These new powers need to be tested in the courts and the government should back enterprising councils to use them. If reasonable attempts by a local authority to purchase land on the open market have been obstructed or ignored,⁹⁴ ministers should swiftly support the bid to remove ‘hope value’. DLUHC should issue guidance on how to use the powers, with examples, to send a strong message to local authorities. DLUHC should also provide funding resources and legal expertise to support local authorities with any legal challenges, and Homes England should work directly with a council to take forward a landmark test case. See Part 2, section 5 on further measures to support councils with CPO use.

The absence of ‘hope value’ proved critical in building new post-war towns. Development corporations bought land at existing use value and sold off parcels to developers, so the uplift in the value of the land, due to inclusion in the new town’s plan, could be reinvested in delivering social housing and vital infrastructure.

The benefits of this model can be very long-term: at Letchworth Garden City, income from leaseholders and rents were used to pay off the loans that funded the town’s development, and then to fund services and improvements to the town over time and continues to accrue to the Treasury.⁹⁵ Keeping the amount paid for land low, means that the benefit of its uplift in value, once developed, goes to the community and can be used directly to fund building social rent homes.

Reform property taxes to help fund social housing and capture land value

A fairer land tax could fund new social homes and ease the unequal tax burden that falls on those with the least property wealth. Most property wealth is held in already developed land, but the tax system has failed to capture huge price increases. The value of land as a proportion of UK GDP grew from 43% in 2001 to 60% in 2022.⁹⁶ Yet the proportion of revenues gathered from property and land taxes remains similar: council tax, business rates and stamp duty on property transactions combined constituted 8.4% of tax take in 2000/1, compared to 8.6% in 2021/22.⁹⁷

Council tax is a hybrid between a property tax and a charge for local services. It is highly regressive relative to income and based on property values that are more than 30 years old. People in the wealthiest parts of England, where land is most expensive, pay less in cash terms and as a proportion of their property value, than people in the least wealthy areas.⁹⁸ Council tax places the burden of payment on occupiers rather than owners. It is therefore very regressive for people on low incomes who are disproportionately likely to be renters, and government cuts since 2010 mean fewer people can get help with paying, even if they are entitled to it.

Making council tax more proportionate to property values would not just be a fairer way to fund local services, it would also offer the opportunity to raise additional, ringfenced revenue for social housing delivery.

Many models of reform have been proposed,⁹⁹ but a radical redesign of the property tax system would offer the greatest opportunity to make it fit to meet the challenge of delivering more social housing. The Proportional Property Tax (PPT), as advocated for by the Fairer Share campaign, would abolish council tax and stamp duty land tax, replacing them with a levy on the cost of a property. Under these proposals, 75% of households would pay less tax than they currently do and payment would shift from occupiers to owners.¹⁰⁰ PPT is also projected to bring up to 600,000 empty and second homes back into use as permanent residences.¹⁰¹ Encouraging owners of long-term empty homes to sell would enable social landlords to buy and convert these properties into social rent homes.¹⁰² The overall level of PPT could also be set to ensure it raises revenue for more social homes, eg. by ringfencing a proportion of the proceeds.

Safeguards would be needed to ensure struggling renters and lower-income households are protected, eg. allowing people to defer liability for the tax until their home is sold.

Fairer taxation should also incentivise landowners and developers to speed up build out. There are estimated to be over a million unbuilt homes with planning permission granted since 2010-11.¹⁰³ The government should empower local authorities to charge council tax (or PPT, if implemented) on every unbuilt development from the point the original planning permission expires, as called for by the Local Government Association (LGA).¹⁰⁴ This would provide additional revenue for delivering social homes as well as discouraging developers from holding onto land for long periods without building.

Create a comprehensive land register to improve land transparency

Changes brought in by the Levelling Up Act to make ownership and control of land more transparent will make it easier for local planning authorities to designate land for new housing, addressing the imbalance of market knowledge between developers and councils. Currently, developers often hold ‘options’ on land, meaning they have the right of first refusal if the land is sold in the future, but these agreements are not always made public.

The Land Registry also remains incomplete, with around 15% of freehold sites not covered, meaning ownership is obscured from public view.¹⁰⁵ This prevents councils, communities and smaller builders from assembling for housing, as it is hard to know who owns plots or whether they are subject to options agreements.

In future, contractual controls on land will need to be registered on the title deed in the Land Registry. By adding details on these controls to the Land Registry, councils will be able to make Local Plans with a far better knowledge of who controls key local sites for housing. The Levelling Up Act also gives the government powers to require registration of land, and utilising those powers to make registration of all sites compulsory, would greatly help identification of ‘grey belt’ sites for new homes.¹⁰⁶ The government could lead the way by producing a national map of publicly owned land.¹⁰⁷

Change land disposal rules to ensure public land is focused on social rent, not sold to the highest bidder

The last government pressured councils to sell off land – a vital resource – for the highest price.¹⁰⁸ The 2022 review of the public land for housing programme showed that just 4% of the homes planned to be built through the life of the programme (2015-2020) were for social rent (5,628 out of 129,000).¹⁰⁹ Public land should be prioritised for social good – and councils should use their land to build social homes.

Release the ‘grey belt’ and ensure councils secure the land value uplift

Our green spaces should be protected. However, a lot of so-called 'green belt,' would be better described as ‘grey belt’ – petrol stations, car parks and brownfield sites inaccurately designated as ‘green’. A sensible approach to green belt release could help solve the land puzzle and help us get more genuinely affordable social homes and make more accessible green spaces at the same time. Critically, arbitrary green belt rules can lock underprivileged communities out of any green space, as the only way to build social housing in many areas is to build up in already densely populated areas.

However, where grey belt land is redesignated for housing, the land value uplift in these areas must not be entirely captured by private actors - councils and the public must benefit from their decision to release green belt. This could be achieved by:

introducing localised land value taxes around green belt areas designated for release.

encouraging councils to use their CPO powers to buy land before they’re redesignated so they can directly capture the land value uplift.

applying the proposed 20% social rent requirement for all large housing developments (set out in Part 2, section 4), to any green belt released for development. Unlocking land for social homes and capturing the benefits of rising land values is crucial to ending the housing emergency in England. Central government must act to ensure the changes brought by the Levelling Up Act lead to more land being available and affordable for homes for social rent.

Unlocking land for social homes and capturing the benefits of rising land values is crucial to ending the housing emergency in England. Central government must act to ensure the changes brought by the Levelling Up Act lead to more land being available and affordable for homes for social rent.

Part 2, section 4: Revitalise and unblock the planning system

In recent years the government has had no clear housing strategy, beyond increasing the number of units. There has been no goal to end homelessness, or clear social housing waiting lists, and no formal aim to improve affordability. This lack of strategy has been most obvious in its haphazard approach to planning reform. We need a functioning planning system that builds the right homes in the right places.

Some developers and landowners say it takes too long to get planning permission for large or complex sites. Local authorities complain that developers fail to build out when they do grant permission, preferring to drip-feed the market to keep prices high. Meanwhile, cash-strapped councils don’t have the resources or expertise to challenge private developers when they claim it’s impossible to build any social homes in their viability assessments. These are symptoms of a broken planning system.

Focus national planning policies on ending homelessness and housing everyone on social housing waitlists

National policies like the Local Housing Need (LHN) assessment, the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), and – when introduced – National Development Management Policies (NDMPs) all hugely impact the type and number of homes built.

Since it was first published in 2012, the NPPF has been updated five times. This constant tinkering causes confusion and delays, as councils and developers scramble to adapt to new rules. A new government must set out its stall on planning reform early on and commit to this long-term. For example, the government could use NDMPs and the NPPF to set minimum levels of social rent and should only override local plans, if they were to result in a more ambitious delivery plan.

The most direct lever to incentivise social housebuilding through the planning system would be to revive and update how the standard method of Local Housing Need is calculated to include the need for social rent homes, calculated on local levels of homelessness and number of households on waiting lists.

The government could then use national policy to ensure local plans are updated to meet this redefined housing need and boost local authorities’ planning capacity. In 2022, 40% of local plans had not been adopted within the previous 5 years.¹¹⁰ An out-of-date plan can result in fewer homes and lead to failures in identifying sufficient land supply, especially for social homes (e.g. through compulsory purchase).

Empower local authorities to challenge developers to deliver more social homes

Since 2013/14, Section 106 planning obligation agreements have delivered 44% of the total 76,295 social rent homes delivered and 43% of all ‘affordable’ units.¹¹¹ But this system can deliver more social homes if we strengthen councils’ ability to challenge developers (and increase build-out speed/overall delivery). There are three key measures to achieve this:

Boost resource funding for Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) so councils can challenge private developers

Local Planning Authorities often struggle to retain and recruit the staff needed to make swift planning decisions, set stronger conditions and ensure private developers deliver their planning obligations. Between 2009/10 and 2019/20, net spending per person on planning by councils fell by 59%, the steepest cut experienced by any local authority service according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.¹¹² This lack of funding severely hampers councils’ ability to plan for the right homes in the right places.Introduce a duty to require 20% onsite delivery of social homes on large sites

Developers price three things into their profit calculations: a) the cost of land; b) the cost of affordable housing contributions and c) the cost of building. In high-value areas, they see costs a) and c) as immovable, but know that they can likely negotiate away b) the cost of affordable housing contributions. However, if councils had a ‘duty to require’ private developers to deliver social rent homes on large sites through legislation or national policies (e.g. National Planning Policy Framework or NDMPs), this calculation would fundamentally change. Knowing that they cannot renege on their Section 106 contributions, developers would be forced to either innovate to reduce build cost (e.g. through MMC) and/or to lower the amount they offer to pay for land (creating a cooling effect in the land market). Critically, onsite delivery of social homes also helps to build mixed communities.Explore top-up grants for distressed developers/sites

Some local authorities already use a grant to top-up Section 106 contributions (although this approach delivers less than 1% of social rent homes).¹¹³ Where a developer is in distress, the top-up grant could be used to convert planned homes into social rent and can reduce the scope for viability to be a barrier for social housing.

Could Planning Contracts offer a route forward?

We need a system that delivers a) the right homes in the right places; b) swift planning decisions and c) ironclad developer contributions. The adversarial approach we have today does not deliver this. One solution is the ‘planning contract’ where the developer and council sign a contract, in which the developer agrees to:

adhere to predefined community engagement principles, design principles and infrastructure requirements

a minimum percentage of social rented homes - delivered early on and onsite

a higher planning fee

deliver in full within an agreed timeframe to hit defined milestones, with sanctions/forfeitures on any failure to deliver (i.e. no reneging)

The council agrees to:

an agreement in principle and fast-track/prioritise any formal approval process

clear service level agreements with sanctions/forfeitures on missed timeframes

invest the higher fee in further planning or delivery capacity.

The legal (and enforcement) mechanism would require further investigation, but the fundamental principle of higher fees, faster approval and non-negotiable commitments, could speed up build-out while securing more effective outcomes for communities and councils.

Reverse some recent planning reforms and change what happens when local authorities fail to build enough homes

Exempt social housing requirements from the ‘tilted balance’

While the LHN formula identifies how many homes a local authority should plan for, the Housing Delivery Test (HDT) assesses whether enough homes have been built by developers/ housing associations etc. in a local area. If only 75% of that target is hit (and regardless of the cause) the local authority is forced to accept a ‘presumption in favour of sustainable development’ on future planning applications. In this scenario, all planning applications must be granted unless the site is protected under the National Planning Policy Framework or the adverse impacts of development significantly outweigh the benefits. This ‘tilted balance’ completely removes locally set affordable housing requirements in favour of the NPPF’s minimum 10% threshold. There is, therefore, also a potential perverse incentive for developers to hold back delivery to trigger this test. At the very least, government should ensure that local affordable housing requirements, which include social rent, are exempt from this ‘tilted balance’.¹¹⁴ ¹¹⁵

Revamp the Brownfield Land Release Fund and reverse recent changes

It is important to build on brownfield land where possible, but recent proposals to apply the tilted balance to brownfield land within England’s main urban areas (even if these local authorities pass the Housing Delivery Test and have up-to-date local plans) are problematic. This would subordinate social rent delivery and could reduce the standard of new housing developments.¹¹⁶ The LGA questions if these reforms would actually be successful in achieving their aim of maximising housing delivery, even when judged independently of the tenure of homes it delivers.¹¹⁷

Instead, government should revamp the Brownfield Land Release Fund.¹¹⁸ The fund provides capital for the acquisition and remediation of brownfield sites, and the delivery of transport infrastructure and placemaking community initiatives. This pot should be increased and made non-competitive and should include a required percentage of social rented homes. This provides fairer access to local authorities and SMEs.

Reverse changes to Permitted Development rights (PDR)

Homes built through Permitted Development don’t go through the usual planning process and are not subject to affordable housing contributions.

Typically, homes built through PDR are of worse quality and fail to meet space standards, as the government’s own report shows.¹¹⁹ ¹²⁰

There are horror stories of private companies using PDR to turn offices into ‘human warehouses’, charging local authorities exorbitant rates for use as terrible-quality temporary accommodation, such as the infamous Terminus House.¹²¹ Despite this, recent governments have extended PDR to fast-track office to residential conversions of any size. As noted in the land section, this could even worsen land affordability if it changes what landowners expect to be paid for their land. Rather than trying to circumvent the planning system, the government should instead incentivise good quality conversion within the planning system by speeding up the process rather than creating carve-outs.

For example, in return for fast approval, the NPPF could require conversions to come with appropriate health and education facilities, and where possible the construction of more social homes.

Reform Section 106, don’t scrap it with an Infrastructure Levy

The Levelling Up and Regeneration Act proposed replacing section 106 with a new ‘infrastructure levy’. The levy would effectively be a tax on the sale of the new private homes built by a developer. Shelter has previously raised concerns that it could disrupt supply as councils and developers adapt to the new system, with no guarantee that it would deliver more social homes. The Infrastructure Levy should not be implemented: instead, the government must empower local authorities to make section 106 fit for purpose. At the very least if the infrastructure levy is adopted, it must be done so in such a way that guarantees it delivers more social rent homes than the system it replaces.

Developer contributions are a vital lever for increasing overall delivery

Shelter’s analysis assumes that an estimated 24,000 social rent homes (around a quarter of the 90K target) could be delivered per year by year five of a delivery plan, using developer contributions. This represents a significant increase from the current number of homes delivered using section 106 (around 3,500 homes), but a reduction in the overall proportion of homes funded using developer contributions (currently around 38%).¹²²

Developer contributions could play a bigger role in the delivery of social rent homes if the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) was amended to require a minimum proportion of social rent homes.¹²³ Arup’s recent analysis estimates that 25,300 social rent homes could be delivered if the NPPF was amended to stipulate that a duty to require a minimum of 20% of homes on larger developments should be for social rent.¹²⁴ Our analysis assumes a slightly more conservative figure for developer contributions to take into account possible challenges with implementation and genuine viability issues. We estimate that around half of the 24,000 homes could be delivered by private developers with councils, housing associations and community groups also benefiting from increased developer contributions.

The housing emergency is caused by a chronic failure of successive governments to build enough social rent homes. ‘Planning reform’ has become a byword for expanding private housing instead of securing genuinely affordable social rent homes. It is time for change. The government must orientate the planning system to maximise social rent.

Part 2, section 5: Boost council house to deliver social homes

Councils will be critical in increasing social rent supply

The government must be ready to commit to a council housebuilding renaissance. Fifty years ago (in 1974), councils directly delivered nearly 100,000 social rent homes.¹²⁵ But, last year, local authorities were only able to directly deliver 8,900 affordable homes, including 2,500 social rent homes.¹²⁶ In 2022/23, only 80 out of 317 local authorities in England directly delivered social homes. The majority (55%) have failed to deliver a single social home in the last five years.¹²⁷

To balance budgets after years of funding cuts, local authorities were forced to shut down their building operations, transfer their council stock to housing associations or focus on building private homes for sale. Council homes sold or demolished have not been replaced – leaving councils with nowhere to house homeless families other than expensive temporary accommodation.¹²⁸

This causes a vicious spiral: the lack of social homes results in rising homelessness, which costs councils millions and in turn, prevents them from prioritising the delivery of genuinely affordable social homes. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Local authorities need a comprehensive plan that addresses the funding and resource challenges, stops the loss of social homes and removes barriers in the land and planning system. The policy interventions outlined in this section could help the new government to deliver 34,000 council social homes a year by 2030.

Shelter commissioned research by Arup, a global engineering, planning and sustainable development firm, to identify interventions that would remove barriers and kickstart a new council-building renaissance. Along with the Commission and Shelter analysis published earlier this year on long-term empty homes, which could help councils achieve the 34,000 target by 2030, there are 10 key measures to remove barriers to council building:

Prioritise the building of social homes in national and local policies – this includes directives set from the most senior levels of government to jump-start a council building programme and adopt pro-social housing policies

Suspend Right to Buy for all new and existing social homes – to protect communities and families that need a genuinely affordable home today and tomorrow, the programme should be suspended

Increase resource funding for councils to recruit and strengthen their in-house expertise - many local councils do not have the appropriate experts or manpower on staff to deliver social homes and need support in filling these gaps

Support Local Planning Authorities to upskill Planning Policy and Development Management Teams – this expertise gap needs to be addressed to get Local Plans in place and to enable speed and efficiency in processing planning applications

Create a new national strategy on land to increase the transparency of what land is available (including 'brownfield' and ‘grey belt’)

Introduce a support package to encourage and enable councils to use their CPO powers - DLUHC and Homes England need to take the lead on supporting councils to use Compulsory Purchase Powers to acquire land, including subsidised legal advice and government-backed liability insurance

Increase AHP funding and restructure AHP rules - to ensure providers can deliver social homes, including local authorities

Make more low-interest loan funding available to councils - so they can borrow more, access lower-interest loans from the Public Works Loan Board, and have longer repayment plans to make building financially viable.

Create a central government programme to support councils coordinate and pool resources together (agglomeration) - to help reduce the cost of building materials and labour, as well as expertise shortage.

Instruct Homes England to adopt a Social Housing Contractor Framework - to provide a platform and the resources for councils to help reduce costs and set some stability for long-term planning, including preapproved suppliers.